Daño renal agudo

Enero 2014

Acute Kidney Injury

David T. Selewski. Pediatrics in Review Vol.35 No.1 January 2014

Abbreviations

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme

AKI: acute kidney injury

AKIN: Acute Kidney Injury Network

ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

ATN: acute tubular necrosis

ECG: electrocardiogram

FEurea: fractional excretion of urea

FENa: fractional excretion of sodium

KDIGO: Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

RIFLE: Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage

Introducción

Injuria renal aguda (AKI), antes llamada insuficiencia renal aguda, se caracteriza por múltiples anomalías, incluyendo aumento de creatinina sérica y del nitrógeno ureico en sangre, alteraciones electrolíticas, acidosis y dificultades con el manejo de fluidos.

Lo que se pensaba previamente que el daño al riñón era relativamente menor puede tener efectos importantes a corto plazo sobre morbilidad y mortalidad y posibles consecuencias a largo plazo para el desarrollo de enfermedad renal crónica. Por lo tanto, el término lesión renal aguda ha reemplazado al de insuficiencia renal aguda, lo que sugiere el espectro de daño renal que puede ocurrir.

Definición

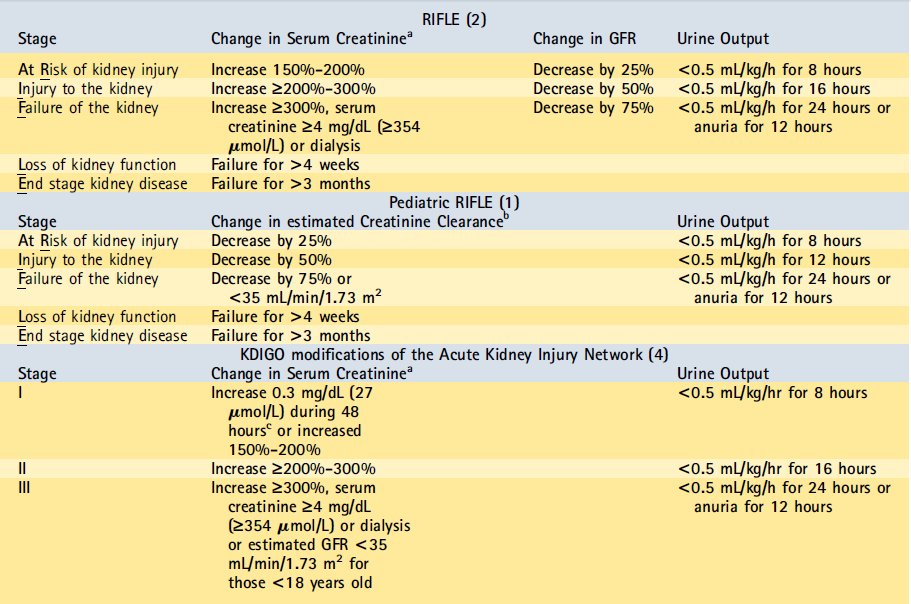

AKI se define clásicamente como una disminución aguda de la tasa de filtración glomerular , la cual causa un aumento en la creatinina sérica . Es importante reconocer las limitaciones de la creatinina como marcador de lesión renal aguda debido a que un aumento en la creatinina puede retrasarse hasta 48 horas después de que ha ocurrido el daño al riñón. A pesar de esta limitación , el cambio en la creatinina sigue siendo el estándar de oro para el diagnóstico de AKI . Ha ocurrido una evolución en la definición de AKI para mejor comprensión, caracterización y estudio del espectro de la enfermedad , que ha tratado de captar la importancia clínica de incluso pequeñas variaciones en la función del riñón. Además , las definiciones previas utilizadas en la literatura eran muy dispares, y esta falta de estandarización hace la comprensión de AKI desafiante . Estas circunstancias han llevado al desarrollo de 2 sistemas para definir AKI pediátrica que se basan en cambios en la creatinina , clearance de creatinina estimado ó débito urinario (diuresis).

La primera de estas definiciones son los criterios de Riesgo, Injuria, Falla, pérdida (Loss) y Etapa Terminal ( RIFLE) pediátricos, los cuales son modificaciones de los criterios de adultos similares.1,2

La segunda es la definición de la Red (network) de Injuria renal Aguda (AKIN ) , que se basa en un aumento de la creatinina a partir de un nivel basal previo.3

El consorcio Enfermedad renal: Mejora Global de Outcomes ( KDIGO ) ha presentado modificaciones para conciliar las diferencias sutiles en los la AKIN adultos y los criterios RIFLE .4 KDIGO es una iniciativa internacional compuesta por expertos que, basado en la revisión sistemática de evidencia , desarrolla y estandariza guías de práctica clínica para niños y adultos con diversas enfermedades renales (incluyendo AKI ) . Actualmente en clínica e investigación, el RIFLE pediátrico y los criterios AKIN modificados se utilizan con mayor frecuencia para definir AKI en los niños (Tabla 1).

Table 1. Schema for Defining Acute Kidney Injury

GFR = glomerular filtration rate; KDIGO = Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; RIFLE = Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage.

aFrom previous trough creatinine. bFor the pediatric RIFLE, change in serum creatinine is the change in estimated creatinine clearance based on the Schwartz equation. cThe remainder of creatinine changes occur during 7 days.

Normal Renal Physiology

Es necesario un conocimiento básico del desarrollo renal y fisiología renal normal para comprender mejor los mecanismos fisiopatológicos de la lesión renal aguda. El riñón es inmaduro al nacer y continúa desarrollándose a temprana edad. Los recién nacidos a término nacen con una dotación completa de nefronas, pero tienen sólo aproximadamente el 25% de sus tasas de filtración glomerular adultos. La función renal de un niño sano aumenta progresivamente, alcanzando una tasa de filtración glomerular madura a los 2 años de edad. Los recién nacidos tienen mecanismos de compensación inmaduros para controlar los cambios en el flujo sanguíneo renal y no son capaces de concentrar completamente su orina.

El flujo sanguíneo renal ayuda a conducir varios procesos fisiológicos , incluyendo la filtración glomerular , la entrega de oxígeno a los riñones , y la reabsorción de agua y solutos . El flujo sanguíneo renal está bajo complejo control por una combinación de hormonas y mecanismos reflejos . Las arteriolas aferentes y eferentes controlan el flujo sanguíneo renal hacia y desde el glomérulo , respectivamente . El stretch de estas arteriolas (retroalimentación miogénica) y la entrega de cloruro de sodio detectada por el aparato yuxtaglomerular (retroalimentación túbulo glomerular ) conducen una serie de respuestas hormonales sistémicas y locales al bajo flujo sanguíneo renal.

En caso de perfusión renal disminuída, se produce vasodilatación arteriolar aferente en respuesta a prostaglandinas (prostaglandinas E e I ) , óxido nítrico y bradiquininas para mantener la filtración glomerular y el flujo sanguíneo renal. Al mismo tiempo , la arteriola eferente se contrae reflejamente por activación nerviosa simpática, endotelina y activación del sistema renina-angiotensina, que causa producción de angiotensina II .

Estos mecanismos funcionan concertadamente para mantener la filtración glomerular y el flujo sanguíneo renal . Los estados de enfermedad y ciertas intervenciones médicas pueden interferir con estos mecanismos , causando efectos negativos sobre la filtración glomerular. Además, algunos de estos mecanismos compensatorios, cuando están estresados más allá de parámetros normales , pueden ellos mismos causar disminución de diuresis y hallazgos clínicos que uno asociaría con AKI . En caso de perfusión renal disminuída, varios de estos mecanismos compensatorios también dirigen la reabsorción de sodio y agua para aumentar el volumen extracelular . La actividad aumentada del sistema renina-angiotensina y la producción de angiotensina II ( activa en el túbulo proximal ) causan un aumento de secreción de aldosterona ( activa en el túbulo distal ) , lo que causa aumento de la reabsorción de sodio . El aumento de la actividad nerviosa simpática también regula la reabsorción de sodio. La reabsorción de urea y agua es dirigida por la hormona antidiurética.

La actividad de estos mecanismos reflejos explica diversos cambios en las concentraciones de electrolitos urinarios y hallazgos clínicos que ayudan a diferenciar las causas de AKI. La inmadurez de estos mecanismos en el recién nacido también explica por qué el diagnóstico y la evaluación de la causa de AKI en el neonato difiere de la de niños mayores.

Epidemiología

The epidemiology of AKI has evolved over the years and reflects the patient population under study. In developing countries the most common causes of AKI continue to be volume depletion, infection, and primary renal diseases (hemolytic uremic syndrome, glomerulonephritis).

In developed countries, volume depletion and primary renal disease remain common causes of AKI in previously healthy children. In hospitalized children in developed countries, particularly in tertiary care centers, there has been a shift in the etiology of AKI from primary renal disease to secondary causes of AKI that are oftenmultifactorial in nature and often complicate another diagnosis or its treatment (eg, heart disease, sepsis, and nephrotoxic drug exposure). (5) Despite this shift in epidemiology, an ordered approach to the diagnosis of AKI divides the potential origins into prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal causes.

La epidemiología de AKI ha

evolucionado con los años y refleja la población de pacientes en estudio. En los

países en desarrollo las causas más comunes de lesión renal aguda siguen siendo

depleción de volumen, infección y enfermedades renales primarias (síndrome

urémico hemolítico, glomerulonefritis).

En los países desarrollados, la depleción de volumen y la enfermedad renal

primaria siguen siendo las causas más comunes de lesión renal aguda en niños

previamente sanos. En los niños hospitalizados en los países desarrollados,

especialmente en los centros de atención terciaria, se ha producido un cambio en

la etiología de la lesión renal aguda de la enfermedad renal primaria de causas

secundarias de AKI que son oftenmultifactorial en la naturaleza y, a menudo

complican otro diagnóstico o su tratamiento (por ejemplo, las enfermedades del

corazón , sepsis, y la exposición al fármaco nefrotóxico). (5) A pesar de este

cambio en la epidemiología, un enfoque ordenado para el diagnóstico de AKI

divide los orígenes potenciales de las causas pre-renales, intrínsecos, y

post-renales.

Fisiopatología de AKI

AKI prerenal

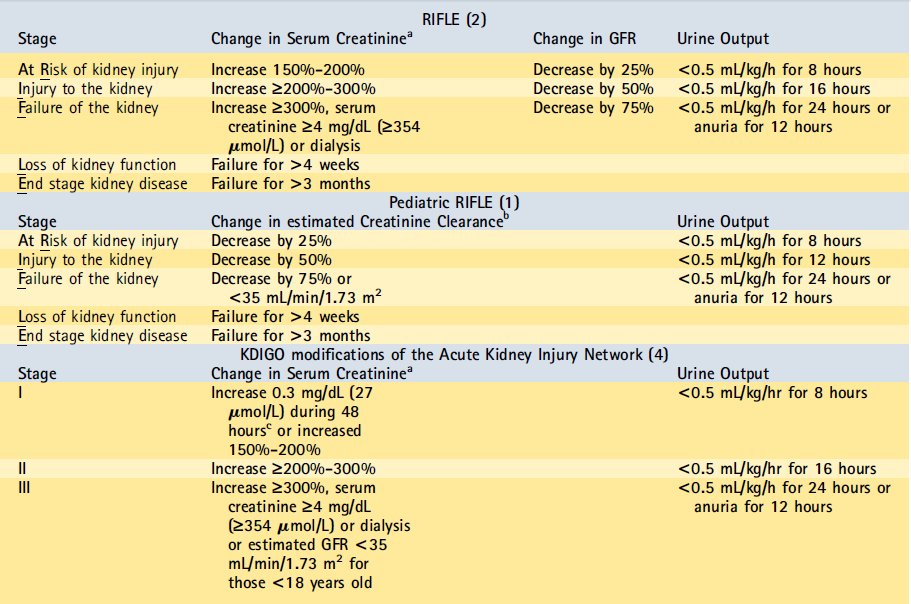

Prerenal AKI results from a decrease in renal blood flow, leading to hypoperfusion (Table 2). The underlying pathophysiologic states may be due to a decrease in effective circulating volume, loss of vascular tone, or decreased cardiac output or blood delivery to the kidneys. Renal losses, gastrointestinal tract losses, or hemorrhage can lead to direct reduction in volume and decreased renal perfusion. Alternatively, a redistribution of fluid may occur from either reduced oncotic pressure within the blood (low albumin from liver disease, nephrotic syndrome, or protein losing enteropathy) or increased leak from vessels (systemic inflammatory response syndrome or sepsis), leading to suboptimal renal perfusion. Systemic vasodilation or poor vascular tone complicates a number of illnesses in critically ill children and may result in hypoperfusion of the kidneys. Finally, there may be a decrease in the delivery of blood to the kidneys because of an overall decrease in cardiac output (underlying heart disease or myocarditis) or increased resistance to flow (abdominal compartment syndrome or renal artery stenosis). In practice, previously healthy children frequently present with a decreased effective circulating volume from a single cause, whereas chronically ill or hospitalized children may have multifactorial processes.

Prerrenal AKI resulta de una disminución en el flujo sanguíneo renal , lo que lleva a la hipoperfusión ( Tabla 2 ) . Los estados patofisiológicos subyacentes pueden ser debido a una disminución en el volumen circulante efectivo , la pérdida del tono vascular , o disminución del gasto cardíaco o la entrega de sangre a los riñones . Pérdidas renales , pérdida del tracto gastrointestinal o hemorragia pueden conducir a una reducción directa en el volumen y la disminución de la perfusión renal. Alternativamente , una redistribución de fluidos puede ocurrir por cualquiera de disminución de la presión oncótica en la sangre ( albúmina baja por enfermedad hepática , síndrome nefrótico o enteropatía perdedora de proteínas ) o el aumento de fugas de los vasos ( síndrome de respuesta inflamatoria sistémica o sepsis) , que conduce a la perfusión renal subóptima . Vasodilatación sistémica o pobre tono vascular complica una serie de enfermedades en los niños críticamente enfermos y pueden dar lugar a la hipoperfusión de los riñones. Finalmente , puede haber una disminución en el suministro de sangre a los riñones debido a una disminución global del gasto cardíaco ( enfermedad cardíaca subyacente o miocarditis) o aumento de la resistencia al flujo ( síndrome compartimental abdominal o estenosis de la arteria renal ) . En la práctica , los niños previamente sanos presentan frecuentemente con un volumen circulante efectivo disminuido de una sola causa , mientras que los niños con enfermedades crónicas o hospitalizados pueden tener procesos multifactoriales.

Tabla 2.- Causas de AKI prerenal

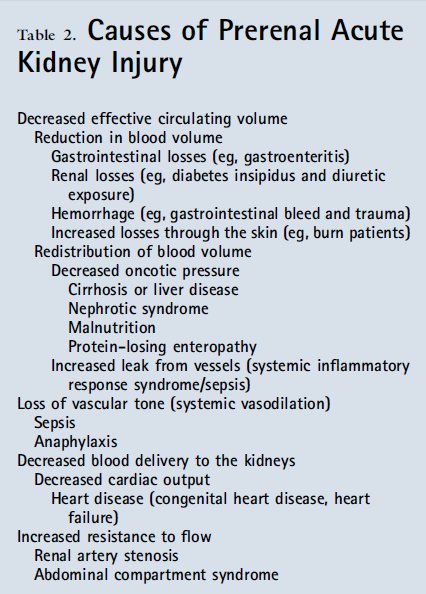

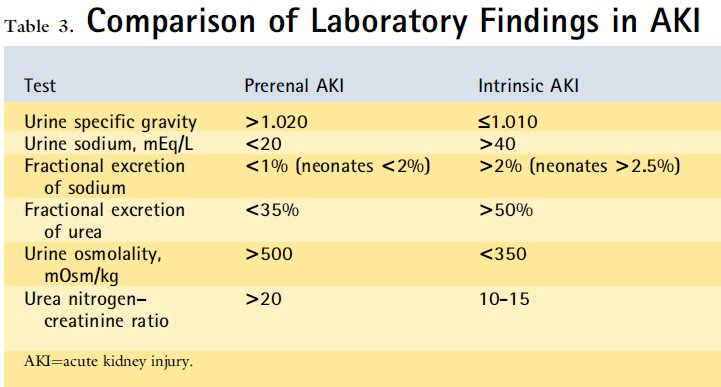

As noted above, low renal blood flow stimulates compensatory mechanisms, including increased sympathetic tone, activation of the renin- angiotensin system, release of antidiuretic hormone, and local paracrine activities (prostaglandin release). In the prerenal state, the afferent arterioles vasodilate in response to the local effects of prostaglandins in an effort to maintain renal blood flow and glomerular filtration. Consequently, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, in volume-depleted children may worsen AKI by preventing this compensatory afferent arteriolar vasodilation. At the same time, angiotensin II causes efferent arteriolar constriction. Interruption of this compensatory mechanism by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors predisposes patients to prerenal AKI. The effects of renin- angiotensin system activation and antidiuretic hormone release result in increased sodium and urea reabsorption, respectively. The reabsorption of sodium, urea, and water leads to oliguria and the characteristic urine findings in prerenal AKI (Table 3).

Como se señaló anteriormente , el flujo sanguíneo renal bajo estimula los mecanismos de compensación , incluyendo el aumento del tono simpático, la activación del sistema renina- angiotensina, la liberación de la hormona antidiurética , y actividades paracrinas locales ( la liberación de prostaglandinas ) . En el estado prerrenal , las arteriolas aferentes dilatan en respuesta a los efectos locales de las prostaglandinas en un esfuerzo para mantener el flujo sanguíneo renal y la filtración glomerular . En consecuencia , los fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINE) , como el ibuprofeno , en los niños con depleción de volumen pueden empeorar AKI previniendo esta compensatoria vasodilatación arteriolar aferente. Al mismo tiempo , la angiotensina II causa la constricción arteriolar eferente . La interrupción de este mecanismo de compensación por la enzima convertidora de angiotensina (IECA) predispone a los pacientes a prerrenal AKI . Los efectos de la activación del sistema renina-angiotensina y el resultado de la liberación de hormona antidiurética en aumento de la reabsorción de sodio y urea , respectivamente . La reabsorción de sodio , la urea , y el agua conduce a oliguria y los hallazgos de orina característicos en prerrenal AKI ( Tabla 3 )

Table 3. Comparación de hallazgos de laboratorio en AKI

Neonates are a special group when considering prerenal AKI. Neonates have increased insensible losses because of a high body surface area to mass ratio, which can be exacerbated by the use of radiant warmers for critically ill newborns. Neonates are further at risk for prerenal AKI due to immature compensatory mechanisms, including poor urine concentrating abilities. This inability to concentrate urine explains why AKI in neonates is often nonoliguric, making its recognition more difficult.

Patients with sickle cell disease are predisposed to prerenal AKI because of a number of pathophysiologic mechanisms inherent to the disease that may affect the kidney. The renal medulla represents an area of the kidney at risk in sickle cell disease because of a low oxygen concentration and high tonicity; this predisposes patients to sickling. Repeated episodes of sickling in the renal medulla result in vascular congestion and the loss of vasa recta of the juxtaglomerular nephrons, which can lead to chronic interstitial fibrosis and urine concentrating defects. In early childhood, the urinary concentrating defects frequently are reversible with treatment of the sickle cell disease but can progress to chronic concentrating defects over time.

Los recién nacidos son un grupo

especial al considerar prerrenal AKI . Los recién nacidos se han incrementado

las pérdidas insensibles debido a una superficie corporal de alta a masa , que

puede ser agravada por el uso de los calentadores radiantes para recién nacidos

críticamente enfermos . Los recién nacidos son más en riesgo de AKI prerrenal

debido a los mecanismos de compensación inmaduros , incluyendo pobres

habilidades de orina para concentrarse. Esta incapacidad para concentrar la

orina , explica por qué la IRA en los recién nacidos a menudo no oligúrica , por

lo que su reconocimiento sea más difícil.

Los pacientes con enfermedad de células falciformes están predispuestos a

prerrenal AKI debido a una serie de mecanismos fisiopatológicos inherentes a la

enfermedad que puede afectar a los riñones. La médula renal representa un área

del riñón en riesgo en la enfermedad de células falciformes a causa de una

concentración de oxígeno baja y alta tonicidad ; este predispone a los pacientes

a formación de células falciformes . Los episodios repetidos de formación de

células falciformes en el resultado médula renal en la congestión vascular y la

pérdida de los vasa recta de las nefronas yuxtaglomerulares , que pueden

conducir a la fibrosis intersticial crónica y concentración de la orina defectos

. En la primera infancia , los defectos de concentración en orina con frecuencia

son reversibles con el tratamiento de la enfermedad de células falciformes ,

pero puede progresar a defectos de concentración crónicas a través del tiempo

Intrinsic AKI

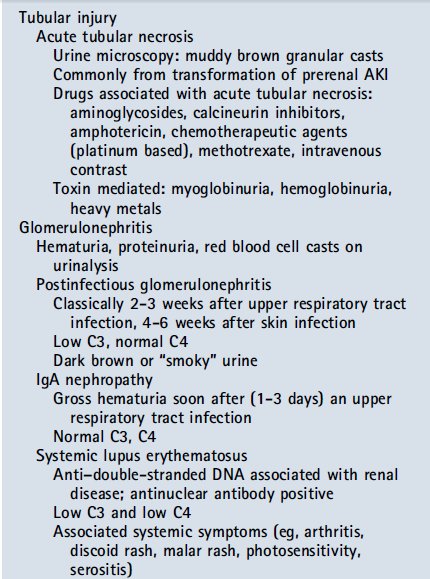

Intrinsic AKI refers to direct renal parenchymal damage or dysfunction. Categories include AKI associated with tubular, interstitial, glomerular, or vascular damage and nephrotoxin exposure (Table 4).

AKI intrínseca se refiere a dirigir daño del parénquima renal o disfunción. Las categorías incluyen AKI asociado con tubular, intersticial, glomerular, o daño vascular y la exposición nefrotoxina (Tabla 4)

Table 4. Causes of Intrinsic AKI

The most common cause of intrinsic AKI in tertiary care centers is transformation of prerenal AKI to acute tubular necrosis (ATN) after prolonged hypoperfusion. The areas of the kidney that are most susceptible to damage with prolonged renal hypoperfusion include the third segment of the proximal tubule (high energy requirement) and the region of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle located within the medulla (low oxygen tension in the medulla). The damage seen from prolonged hypoperfusion can range from mild tubular injury to cell death. As cellular necrosis occurs, debris may build up in the tubules and further block tubular flow. Tubular dysfunction, a frequent hallmark of ATN, will not be evident during periods of oliguria but may become apparent during the recovery phase.

In previously healthy children, glomerular and vascular causes of intrinsic AKI are more common. Where there is concern for glomerulonephritis, the clinical presentation and timing often suggest the origin, including isolated glomerulonephritides (eg, postinfectious glomerulonephritis) and multisystem immune complex–mediated processes that involve the kidney (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus). Vascular causes of intrinsic AKI include microangiopathic processes (hemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura) and systemic vasculitides that involve larger vessels.

La causa más común de lesión

renal aguda intrínseca en los centros de atención terciaria es la transformación

de prerrenal AKI a necrosis tubular aguda (NTA ), después de hipoperfusión

prolongada. Las áreas del riñón que son más susceptibles al daño con

hipoperfusión renal prolongada incluyen el tercer segmento del túbulo proximal (

alto requerimiento de energía) y la región de la rama gruesa ascendente del asa

de Henle ubicado dentro de la médula ( baja tensión de oxígeno en la médula) .

El daño observado de hipoperfusión prolongada puede variar de lesión tubular

leve a la muerte celular . Como se produce la necrosis celular , desechos pueden

acumularse en los túbulos y aún más el flujo de bloque tubular. Disfunción

tubular , una característica frecuente de la ATN , no será evidente durante los

períodos de oliguria sino que se manifiesta durante la fase de recuperación .

En niños previamente sanos , causas glomerulares y vasculares de AKI intrínseca

son más comunes. Donde hay preocupación por la glomerulonefritis , la

presentación clínica y el momento sugieren a menudo el origen, incluyendo

glomerulonefritis aislados ( por ejemplo, glomerulonefritis post-infecciosa ) y

procesos mediados por complejos inmunes multisistémicas que incluyen el riñón

(por ejemplo , lupus eritematoso sistémico) . Causas vasculares de la IRA

intrínseca incluyen procesos microangiopáticas (síndrome urémico hemolítico y

púrpura trombocitopénica trombótica ) y vasculitis sistémicas que involucren a

los buques más grandes

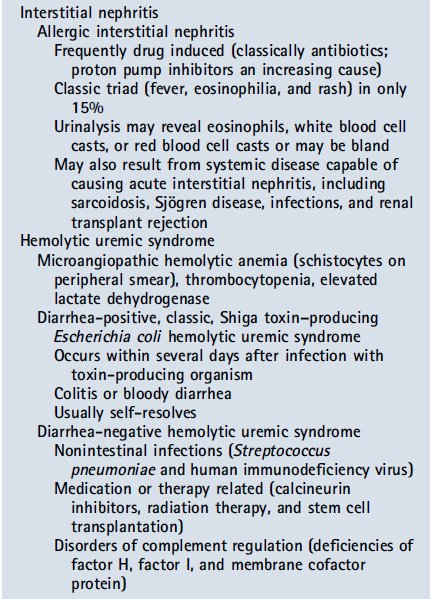

Acute interstitial nephritis occurs after exposure to an offending agent, such as certain medications, including antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, and diuretics. Signs and symptoms may develop 3 to 5 days after a second exposure to as long as weeks to months after an initial exposure. Drugs can cause AKI in ways other than acute interstitial nephritis. Nephrotoxin exposure is an increasingly common cause of intrinsic AKI, particularly in hospitalized patients. As previously mentioned, drugs such as NSAIDs and ACE inhibitors can contribute to AKI by inhibiting renal vascular autoregulation. Other common drugs implicated in AKI include aminoglycosides, amphotericin, chemotherapeutic agents (cisplatin, ifosfamide, and methotrexate), and calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Radiocontrast agents are a significant cause of nephrotoxinrelated AKI; newer iso-osmolar agents are somewhat less nephrotoxic, but the risk remains. In instances of massive hemolysis or rhabdomyolysis, endogenous elements, such as myoglobin and hemoglobin, can obstruct tubules and/or cause direct toxic effects to the kidney.

Nefritis intersticial aguda ocurre después de la exposición a un agente agresor , como ciertos medicamentos, incluyendo antibióticos, inhibidores de la bomba de protones, los AINE y los diuréticos . Los signos y síntomas se pueden desarrollar de 3 a 5 días después de una segunda exposición a mayor tiempo de semanas a meses después de la exposición inicial. Las drogas pueden causar AKI de maneras distintas a nefritis intersticial aguda. Exposición nefrotoxina es una causa cada vez más frecuente de lesión renal aguda intrínseca , sobre todo en los pacientes hospitalizados. Como se mencionó anteriormente , los medicamentos como los inhibidores de la ECA y AINE pueden contribuir a AKI inhibiendo la autorregulación vascular renal. Otros medicamentos comunes implicados en AKI incluyen aminoglucósidos, anfotericina , agentes quimioterápicos ( cisplatino , ifosfamida y metotrexato ) , y los inhibidores de la calcineurina (ciclosporina y tacrolimus) . Radiocontraste agentes son una causa significativa de nephrotoxinrelated AKI ; agentes isoosmolares nuevos son algo menos nefrotóxico , pero el riesgo sigue siendo . En los casos de hemólisis masiva o rabdomiólisis , elementos endógenos, como la mioglobina y hemoglobina , pueden obstruir los túbulos y / o causar efectos tóxicos directos a los riñones.

Postrenal AKI

Postrenal AKI results from obstructive processes that block urine flow. Acquired causes of urinary tract obstruction include those that result from local mass effect (bilateral ureteral obstruction by a tumor), renal calculi, or clots within the bladder.

Posrenal AKI resulta de procesos obstructivos que bloquean el flujo de orina. Las causas adquiridas de obstrucción del tracto urinario incluyen los que resultan de efecto de masa locales (obstrucción ureteral bilateral por un tumor), cálculos renales, o coágulos dentro de la vejiga

The Renal Angina Concept and Early Identification of AKI

An important developing paradigm in the study and treatment of AKI is the idea of renal angina, a term used to describe a high-risk state that occurs before AKI. (6) Earlier recognition of a prerenal state defines a period before significant parenchymal damage (eg, the development of ATN) where AKI can be reversed. Furthermore, patients who are identified as being at risk may have nephrotoxic medications held or dosages adjusted to potentially prevent the development of intrinsic AKI. Research using renal angina scoring systems is an active area that aims to identify patients at risk for AKI. Concurrently, investigation is under way to study novel biomarkers (urine neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin and urine kidney injury molecule 1) that will allow for the earlier identification of kidney injury in critically ill children (often up to 48 hours before an increase in creatinine) to allow prevention and potentially earlier intervention.

Un paradigma de desarrollo importante en el estudio y tratamiento de la IRA es la idea de la angina renal, un término usado para describir un estado de alto riesgo que se produce antes de AKI. (6) A principios de reconocimiento de un Estado prerrenal define un período antes de daño del parénquima significativa (por ejemplo, el desarrollo de la ATN) donde AKI se puede revertir. Además, los pacientes que son identificados como de riesgo pueden tener medicamentos nefrotóxicos celebradas o las dosis ajustadas a potencialmente impiden el desarrollo de la IRA intrínseca. La investigación que utiliza los sistemas de puntuación de angina renal es un área activa que tiene como objetivo identificar a los pacientes en riesgo de AKI. Al mismo tiempo, la investigación está en curso para estudiar nuevos biomarcadores (neutrófilos orina lipocalina asociada a gelatinasa y la orina del riñón molécula lesión 1) que permitan la identificación temprana de la lesión renal en niños críticamente enfermos (a menudo hasta 48 horas antes de un aumento de la creatinina) para permitir la prevención y la intervención potencialmente anterior

Diagnosis of AKI

A detailed history and physical examination are invaluable for children who develop AKI. Quantifying the urine output during the previous several days may provide insight to the cause and severity of the episode of AKI and serves to categorize the event as oliguric (defined as urine output <1 mL/kg/h) or nonoliguric. Systematic evaluation of potential prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal causes is key to diagnosing the origin of AKI. Frequently, the history will provide insight into causes or risk factors for prerenal AKI, including decreased circulatory volume (gastroenteritis and hemorrhage), redistribution of circulatory volume (edematous states, nephrotic syndrome, and sepsis), decreased cardiac output (heart disease), or increased resistance to blood flow (abdominal compartment syndrome and renal artery stenosis). In previously healthy children, the history and physical examination may offer clues (Table 4) to the underlying intrinsic renal origin, including volume depletion, recent viral illness or sore throat (possibly consistent with acute glomerulonephritis), rashes, swollen joints (suggesting systemic disorders such as lupus), hematuria, or medication exposures. In newborns with a suspected obstruction, a good prenatal history is important. For example, abnormalities on fetal ultrasonogram, including enlarged bladder, hydronephrosis, or decreased amniotic fluid, may suggest posterior urethral valves in a male infant.

When evaluating AKI, it is important to remember that an increase in creatinine typically occurs up to 48 hours after renal injury and may reflect events that occurred 2 to 3 days earlier. Therefore, it is important to review episodes of hypotension, hypoxia, sepsis, surgery, contrast exposures, and drug exposures that occur 48 to 72 hours before the episode of AKI becomes apparent. As part of the initial evaluation for AKI, patients should have the following tests performed: basic electrolyte panel, serum creatinine measurement, urinalysis, urine sodium measurement, urine urea measurement, urine creatine measurement, urinalysis, and a renal ultrasound study. Frequently, urine studies will allow differentiation between prerenal AKI and intrinsic AKI (eg, ATN). Typical laboratory findings for prerenal AKI include a normal urinalysis result, concentrated urine (osmolality >500 mOsm/kg [>500 mmol/kg]), fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) less than 1% (<2% in neonates), fractional excretion of urea (FEurea) less than 35%, urine sodium less than 20 mEq/L (<20 mmol/L), and urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio greater than 20 (Table 3). A loss of urine concentrating ability is classically seen in ATN and results in the characteristic urine studies that differentiate it from prerenal AKI (Table 3). Urinalysis with accompanying urine microscopy can be illuminating and point toward particular diagnostic categories. Muddy granular casts on microscopy suggest ATN; red blood cell casts suggest glomerulonephritis. A urinalysis positive for blood on dipstick evaluation without evidence of red blood cells on microscopy should raise concerns for hemoglobinuria (hemolysis) or myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis).

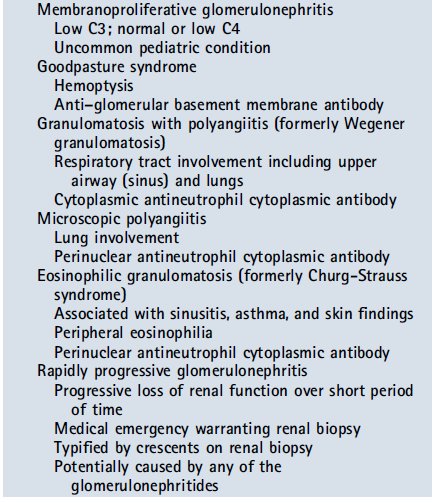

The presence of hematuria, proteinuria, and/or red blood cell casts in the right clinical scenario should raise concern for possible glomerulonephritis. In the context of a recent upper respiratory tract infection, one should consider the diagnosis of postinfectious glomerulonephritis (classically with pharyngitis 2-3 weeks earlier or skin infections 4-6 weeks earlier) and should evaluate serum complements (low C3 and normal C4). In patients with a more recent upper respiratory tract infection (2-3 days) with gross hematuria on urinalysis, one must consider IgA nephropathy (normal complement levels). A urinalysis consistent with glomerulonephritis in the context of the appropriate systemic symptoms (eg, rash and arthritis) may point toward systemic lupus erythematosus (low C3 and low C4) and may warrant further antibody testing (antinuclear and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies).

If there is involvement of the pulmonary system (cough, infiltrate on radiographs, and hemoptysis) and evidence of active glomerulonephritis, the pulmonary renal syndromes should be considered. These syndromes include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis and cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody [ANCA]), microscopic polyangiitis (perinuclear ANCA), eosinophilic granulomatosis (formerly Churg-Strauss Syndrome and perinuclear ANCA), and Goodpasture syndrome (anti–glomerular basement membrane antibody). A more detailed description of glomerulonephritides is beyond the scope of this review. In the setting of a classic clinical and laboratory presentation of postinfectious glomerulonephritis, a renal biopsy is not warranted, but to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment of the remaining glomerulonephritides, a biopsy is necessary. Each of the glomerulonephritides is capable of causing rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, which is defined by rapidly increasing blood urea nitrogen and creatine levels. In this scenario, a renal biopsy and treatment are immediately warranted because irreversible renal injury may develop without prompt intervention.

The classic triad for allergic interstitial nephritis of fever, rash, and eosinophilia is not often seen in the modern era and is observed in less than 15% of patients. This is due to a change over time in the most common offending agents. In patients with suspected interstitial nephritis, there is frequently bland urine sediment that does not have red blood cell casts but may have white blood cell casts present. The classic finding is urine eosinophils, although this is not universal. There can be varying degrees of proteinuria; NSAID-associated interstitial nephritis is capable of causing nephrotic range proteinuria. A renal biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If a patient has a recent history of diarrheal illness, low platelet counts, and hemolytic anemia with AKI, one should consider hemolytic uremic syndrome. In the appropriate setting, a peripheral blood smear with schistocytes is confirmatory. In recent years there has been an increase in the recognition of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by nondiarrheal infections (eg, Streptococcus pneumonia or human immunodeficiency virus) or genetic abnormalities in complement regulatory components (eg, factor H or factor I); a high index of suspicion is necessary, and specialty consultation is warranted.

Imaging plays a small role in the diagnosis of intrinsic renal disease. Kidney size, measured by renal ultrasonography, can provide information about the duration of the disease. Larger kidneys point toward an acute process that involves active inflammation. Kidneys that are particularly small for age may suggest a more chronic process. Often the kidneys will demonstrate increased echogenicity in the setting of AKI, which is a nonspecific finding. A Doppler evaluation of the renal vasculature is an important initial step if there are concerns of renal artery stenosis, but if the result of the evaluation is negative and concern of renal artery stenosis remains, further studies should be considered in consultation with a pediatric nephrologist. Imaging by renal ultrasonography to demonstrate hydronephrosis is the most important initial step in the diagnosis of an obstructive process and may provide clues to the anatomical location of the obstruction. For example, bilateral hydronephrosis suggests a more distal obstruction. If an obstructive process is diagnosed, one should relieve the obstruction immediately.

Manejo de AKI

The most important management principle for children with AKI is prevention. In both the outpatient settings and the hospital this can be achieved by identifying children who are at risk for developing AKI. In outpatient pediatrics it is important to ensure adequate hydration and be mindful of medications children may take in the short term (NSAIDs) or long term (diuretics and ACE inhibitors) that increase the risk of AKI. In hospitalized patients, it is also important to be mindful of daily volume status, nephrotoxic medications, or nephrotoxic exposures. For patients at risk for developing AKI, it is important that the team evaluates all potentially nephrotoxic medications, reviews prescribed doses, actively considers alternatives, and monitors levels of medications such as gentamicin and vancomycin.

Manejo de fluídos y electrolitos

The initial step in the treatment of children who present with oliguria, hypotension, or instability is to restore intravascular volume. An initial 20 mL/kg bolus of isotonic fluids should be given rapidly (in minutes if necessary in the setting of shock). Isotonic fluids that may be used for short- term volume expansion include normal saline, lactated Ringer solution, albumin, and packed red blood cells. The choice of fluid depends on the clinical scenario, but normal saline is most commonly used. This treatment should be repeated according to the Pediatric Advanced Life Support algorithms. (7)

In children with underlying or suspected cardiac disease, smaller initial fluid boluses (10mL/kg)may be given repeatedly, as indicated, for longer periods; this will permit appropriate resuscitation while reducing the risk of unintentional volume overload, which could be problematic in the setting of heart disease. During the fluid resuscitation process, repeated reevaluation is necessary for all children to monitor for signs of fluid overload (pulmonary or peripheral edema) and response (improved vital signs and urine output).

After adequate fluid resuscitation, early initiation of vasopressor support may be indicated; vasopressor support may be required sooner for a child who presents with obvious fluid overload. Studies in adults evaluating low renal dose dopamine have found no benefit; dopamine at these low doses does not increase or preserve urine output or improve the outcome of AKI. Vasopressor support should be provided to ensure adequate renal perfusion with the choice of vasopressor based on the clinical scenario.

Once the patient has been adequately fluid resuscitated, one may consider a trial of diuretics (furosemide) if the patient remains oliguric. The literature reports mixed results for diuretics in patients with oliguria. The literature surrounding the use of mannitol is inconclusive, and this medication may be associated with serious adverse effects (increased serum osmolarity, pulmonary edema, and AKI). The use of mannitol to ensure urine output is not recommended.

In children who remain oliguric after intravascular volume resuscitation, conservative fluid management may be necessary. In these children, one may restrict fluid to insensible fluid losses (300-500 mL/m2/d). Individuals with AKI are subject to a number of electrolyte disturbances, including dysnatremias, hyperkalemia, acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia.

Typical sodium requirements in healthy children are 2 to 3 mEq/kg/d, but management should be individualized in children with AKI, with adjustments made based on frequent monitoring. Excessive sodium input should be avoided to prevent hypertension and other complications of sodium overload. Potassium and phosphorous should be withheld from fluids in these patients to avoid the risks of iatrogenic overload. Potassium and phosphorous will need to be replaced intermittently as necessary because low levels of potassium (cardiac conduction abnormalities) and phosphorous (poor muscle contraction) can have detrimental implications in critically ill children. Inability to maintain biochemical or fluid balance in AKI patients represents an indication for renal replacement therapy.

Hyperkalemia remains one of the most recognized complications of AKI. The presenting symptoms of hyperkalemia are frequently nonspecific, including fatigue, weakness, tingling, nausea, and even paralysis. For this reason, limiting potassium intake and diligent monitoring of laboratory test results in children with AKI are important. The most serious manifestation of hyperkalemia is cardiac conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias. Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes may be noted when potassium levels are 6.5 to 7 mEq/L (6.5-7 mmol/L), but there can be significant variability, depending on the clinical circumstances. In pathophysiologic states of increased potassium release from cells (tumor lysis syndrome and rhabdomyolysis), ECG changes may occur at lower levels. The potassium levels that result in ECG changes fluctuate with the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, acuity, and associated electrolyte abnormalities (hypocalcemia).

The ECG changes are typified first by peaked T waves. Other ECG changes may include widened QRS, flattened p waves, and prolonged PR interval. Untreated hyperkalemia may lead to life- hreatening arrhythmias.

In patients with potassium levels greater than 6 mEq/L (>6 mmol/L), one should obtain an ECG. If potassium levels are 5.5 to 6.5 mEq/L (5.5-6.5 mmol/L) and the patient has an appropriate urine output without any abnormalities on ECG, one may consider treatment with a resin that binds potassium in the gut (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) or a saline bolus with furosemide to reverse any upward trend and slowly bring the potassium back to a more normal range. If there are changes on ECG, a potassium level greater than 7 mEq/L (>7 mmol/L), or a rapidly increasing potassium level in a child with high cell turnover states (eg, tumor lysis and rhabdomyolysis), hyperkalemia should be viewed as life threatening and treated accordingly.

Initial rapid treatment measures include calcium gluconate, which acts to stabilize the cardiac membrane potential and limit the risk of arrhythmia but does not lower potassium levels. This may be followed by the administration of sodium bicarbonate, b2-agonists, and/or insulin with glucose, all of which cause intracellular movement of potassium and subsequent reduction of blood levels, but these do not remove potassium from the body. Sodium bicarbonate may be considered if there is an acidosis associated with the hyperkalemia. Recent trials evaluating sodium bicarbonate therapy in adults with hyperkalemia have not reported efficacy, but this has not been studied in children. Although sodium bicarbonate may be given as part of treatment for hyperkalemia, it should not be the sole therapy. Sodium bicarbonate theoretically acts by shifting potassium intracellularly as it is exchanged for hydrogen ions. b2-agonists, such as albuterol, can be given via nebulizer. This therapy has been reported to lower potassium by 1 mEq/L (1 mmol/L) and is well tolerated but may need to be avoided in children with cardiac issues because tachycardia is a common adverse effect of b2-agonist therapy. Insulin given with glucose drives potassium into cells by increasing sodium and potassium adenosine triphosphatase activity. In conjunction with these various methods, efforts should be made to remove potassium from the body, including loop diuretics with fluid bolus and sodium polystyrene sulfonate. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate should be avoided in neonates or children with underlying bowel disease. If these measures fail, renal replacement therapy should be considered.

The acidosis seen in AKI is characterized by an elevated anion gap, which reflects an inability of the kidneys to excrete acid or reabsorb bicarbonate. With the exception of the treatment of hyperkalemia, use of bicarbonate should be reserved for severe acidosis and administered with great care. Correction of acidosis with bicarbonate can lead to a lowering of ionized calcium (functional hypocalcemia) as hydrogen ions are exchanged on plasma proteins for calcium, which can result in tetany.

Because of a suboptimal glomerular filtration rate in the setting of AKI, hyperphosphatemia can develop, particularly with increased cell turnover (tumor lysis syndrome and rhabdomyolysis). In most circumstances, hyperphosphatemia can be managed conservatively by limiting intake. In patients with hyperphosphatemia, it is important to diligently monitor calcium and ionized calcium levels because ionized hypocalcemia may occur as a result of intravascular binding to excess phosphorus.

Medicamentos

In children with AKI drug clearance may be reduced; daily evaluation of patient medication lists is imperative to avoid iatrogenic drug overdose. Once the kidney function decreases to 50% of normal, most renally excreted drugs will require dose adjustment. Early in episodes of evolving AKI, bedside estimates of kidney function can lead to overestimation of the glomerular filtration rate; careful clinical judgment is required. One should evaluate the appropriateness of administering nephrotoxic medications on a daily basis, consider alternatives, and closely monitor drug levels as able when nephrotoxic medications are unavoidable. When children begin renal replacement therapy, many medication doses must be adjusted further (particularly antibiotics). During episodes of AKI, it is important to manage medication adjustments in a team- based approach that involves pediatric nephrologists and specialized pharmacists.

Nutrition

Typically, AKI is marked by a catabolic state, particularly in critically ill children. The protein requirements in these children may be as high as 3 g/kg/d of amino acids with an accompanying caloric need of 125% to 150% that of healthy children and infants. One should not limit protein delivery as a method to control blood urea nitrogen levels; to ensure adequate protein intake, one may accept a blood urea nitrogen level of 40 to 80 mg/dL (14.3- 28.6 mmol/L). If adequate nutrition and metabolic balance cannot be obtained through conservative measures, this may be an indication for renal replacement therapy.

Renal Replacement Therapy

Renal replacement therapy is considered when conservative measures to manage AKI have failed or are unlikely to be sufficient. Indications for renal replacement therapy include volume overload (10%-20% fluid excess), severe acidosis, hyperkalemia, uremia (typically blood urea nitrogen >100 mg/dL [>35.7 mmol/L] or symptomatic), or an inability to provide adequate nutrition in patients with renal dysfunction. In recent years the importance of volume overload in critically ill children has become apparent, and the degree of fluid overload at the initiation of renal replacement therapy has been found to be associated with increased mortality. (8)(9) Modalities of renal replacement therapy include peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, and continuous renal replacement therapy. The correct choice of modality is a reflection of center-specific expertise, patient characteristics, and clinical situation. Peritoneal dialysis is well tolerated in critically ill children and relatively easy to perform but does not provide the same rate of clearance or ability to manage volume as other modalities. Intermittent hemodialysis performed during 3 to 4 hours provides better clearance but is generally not as well tolerated in critically ill children or children with unstable disease; total daily fluid removal during a short intermittent session can be challenging in these patients. There has been a shift toward continuous renal replacement as the modality of choice in critically ill children. This mode allows for continuous volume and metabolic control spread during 24 hours. Benefits include increased tolerance of fluid removal and improved ability to provide nutrition. Intermittent hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis remain viable options for those patients who require renal replacement but are not critically ill.

Progression to Chronic Kidney Disease and Follow-up

Recent literature has indicated that critically ill children who are discharged after an episode of AKI are at increased risk of chronic kidney disease later in life. (10) (11) Long-term follow-up of these patients is important. The optimal follow-up plan for these children is not clear. In more severe cases of AKI that require renal replacement therapy, follow-up should initially be with specialists. In milder cases, one may consider yearly blood pressure checks and urinalysis.

Summary

On the basis of research evidence and consensus, the term acute kidney injury (AKI) has replaced acute renal failure, suggesting the spectrum of kidney damage that can occur (Table 1). (1)(2)(3)(4)

On the basis of research evidence, in developing countries the most common causes of AKI continue to be volume depletion, infections, and primary renal diseases.

On the basis of research evidence and expert opinion, in developed countries volume depletion and primary renal disease remain common causes of AKI in previously healthy children.

On the basis of research evidence, in hospitalized children, particularly in tertiary care centers, there has been a shift in the etiology of AKI from primary renal disease to secondary causes of AKI that are often multifactorial in nature and often complicate another diagnosis or its treatment (heart disease, sepsis, and nephrotoxic drug exposure). (1)(5)

On the basis of expert opinion, an ordered approach to the diagnosis of AKI divides the potential origins into prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal causes.

On the basis of research evidence, expert opinion, and consensus, patients with AKI are subject to a number of fluid and electrolyte disturbances, including hypervolemia, dysnatremias, hyperkalemia, acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia.

On the basis of research evidence, expert opinion, and consensus, indications for renal replacement therapy include volume overload (10%- 20% fluid excess), acidosis, hyperkalemia, uremia (typically blood urea nitrogen >100 mg/dL [>35.7 mmol/L] or symptomatic), or an inability to provide adequate nutrition in patients with renal dysfunction. (8)(9)

On the basis of research evidence and expert opinion, recent literature has reported that critically ill children who are discharged after an episode of AKI are at increased risk for chronic kidney disease later in life. Long-term follow-up of these patients is important, but the optimal follow-up plan remains unclear. (10)(11)